Coronavirus survivors returning to work could help stop its spread

05/13/2020 / By Franz Walker

Allowing people who have recovered from COVID-19 to go back to work could help reduce its rate of transmission by as much as 77 percent, a new study suggests. The claim comes from a new model developed and analyzed by researchers from the Georgia Institute of Technology (Georgia Tech), Princeton University and McMaster University.

In the study, published in the journal Nature Medicine, the researchers state that this short-term immunity that COVID-19 survivors are presumed to have could help lower the risk of loosening restrictions and restarting economic activity.

“Our model describes ways in which serological tests used to identify individuals who have been infected by and recovered from COVID-19 could help both reduce future transmission and foster increased economic engagement,” said lead author Dr. Joshua Weitz, a professor at the School of Biological Sciences at the Georgia Tech.

“The idea is to think in advance about how identifying recovered individuals could help serve the collective good, using information collected on neutralizing antibodies in new ways.”

“Shield immunity”

Dubbed “shield immunity” by the researchers, this short-term immunity could allow for the reduction of transmission rates even as restrictions on travel and business are lifted.

The researchers studied the impact of presumed immunity in survivors using a computational model of the disease’s epidemiological dynamics, where individuals are categorized as either susceptible, exposed, infectious or recovered.

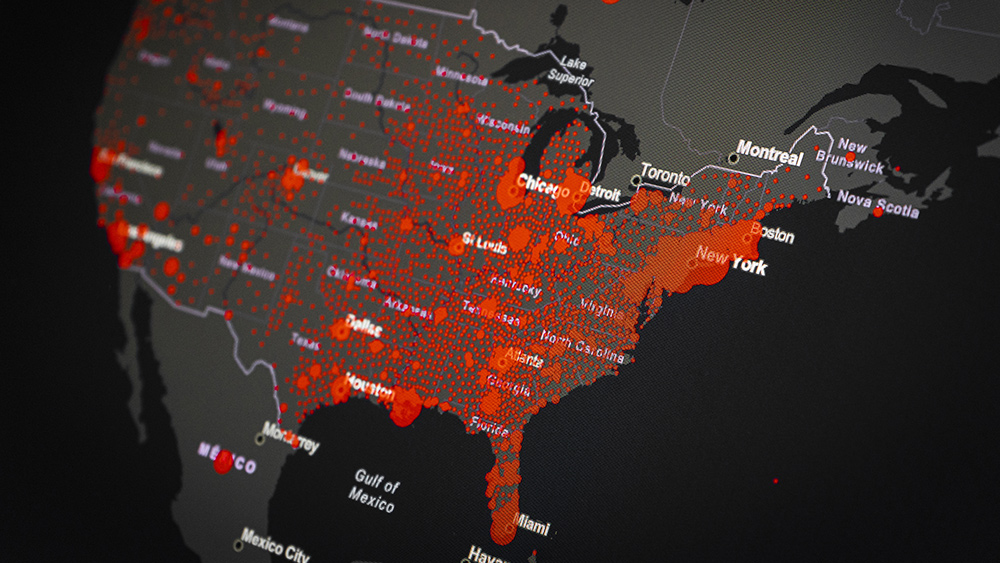

The models predict that in a population of 10 million citizens, the total number of deaths would be brought down from 71,000, without the shielding strategy, to as low as 20,000 if the strategy is implemented aggressively. A less aggressive implementation of the strategy, on the other hand, would bring deaths down to 58,000.

In addition, the model suggests that the effects of social distancing strategies would also be enhanced by shield immunity.

Questions still need to be answered

There are a couple of important caveats to the model, however. Firstly, how long a survivor retains their immunity to COVID-19 remains unknown.

Survivors of related viral infections such as Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) have been demonstrated to retain their antibodies for about two years. Meanwhile, there’s evidence that survivors of Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) keep their immunity for up to three years.

The period of immunity to COVID-19, however, seems to be much shorter. Across the globe, countries are reporting cases of patients who have survived the disease getting reinfected. In South Korea, a country lauded for its response to the pandemic, a number of recovered patients are once again testing positive for COVID-19.

The second caveat is that determining on a broad scale who has the antibodies that provide protection against the coronavirus requires a level of reliable serological testing, which is not yet available in the United States.

Helping restart the economy

The shielding strategy described in the study could bring good news to state governments trying to restart their economies and halt the downturn brought about by measures to stop the pandemic.

A number of U.S. states have already begun to ease restrictions. These have caused some experts, however, to raise alarms about a possible second wave of coronavirus infections that could come later this year, after states reopen.

Some, such as infectious disease expert Dr. Anthony Fauci, have warned that reopening state economies now would come with a human cost. “How many deaths and how much suffering are you willing to accept,” he asked.

Before the researchers’ model can be applied to get Americans back to work, however, the caveats that they have identified must be addressed first. Until such time, any attempts to reopen state economies must be tempered by the need to keep the coronavirus pandemic from spreading more than it already has.

Sources include:

Tagged Under: antibodies, business, coronavirus, covid-19, economy, Flu, herd immunity, immunity, infections, lockdown, outbreak, pandemic, quarantine, research, shield immunity, social distancing, superbugs, virus