6 Steps to treat food poisoning to improve comfort, recovery time, and to limit vomiting

09/15/2025 / By Lance D Johnson

- The CDC’s FoodNet program has stopped tracking six major foodborne pathogens, including Listeria and Vibrio, due to funding cuts — not because outbreaks have declined.

- Experts warn this reduced surveillance could delay detection of outbreaks, putting vulnerable groups (children, the elderly, pregnant women) at higher risk.

- The CDC’s focus on germs ignores the bigger picture: Diet, gut health, and natural immunity play a massive role in whether you get sick — or how severely.

- Processed foods, pesticides, and irradiated ingredients — backed by the same industries that influence the CDC — weaken immune defenses, making us more susceptible to foodborne illnesses.

- A five-step natural pre-treatment plan can mitigate food poisoning symptoms if you act fast, using activated charcoal, ginger, gentian root, and peppermint oil.

The surveillance gap: Why fewer eyes on foodborne threats spells trouble

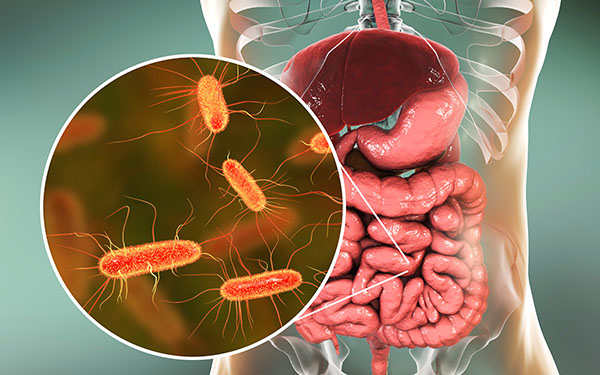

When the CDC’s FoodNet program launched in 1996, it was a landmark effort to track foodborne illnesses in real time. By monitoring outbreaks of Salmonella, Listeria, Campylobacter, and others, the agency could pinpoint contaminated spinach, tainted chicken, or poisoned oysters before they sickened thousands. But now, with funding dried up, FoodNet has quietly stopped tracking six of the eight pathogens it once watched. The remaining two — Salmonella and Shiga toxin-producing E. coli — are just the tip of the iceberg.

“There is no scientific basis for reducing surveillance,” says Lewis Ziska, PhD, an environmental health scientist at Columbia University. “If anything, with climate change altering pathogen behavior and industrial agriculture creating new risks, we should be expanding monitoring.” The CDC’s own data shows foodborne illnesses hospitalize 300,000 Americans annually and kill 5,000. Yet instead of bolstering defenses, the agency is retreating.

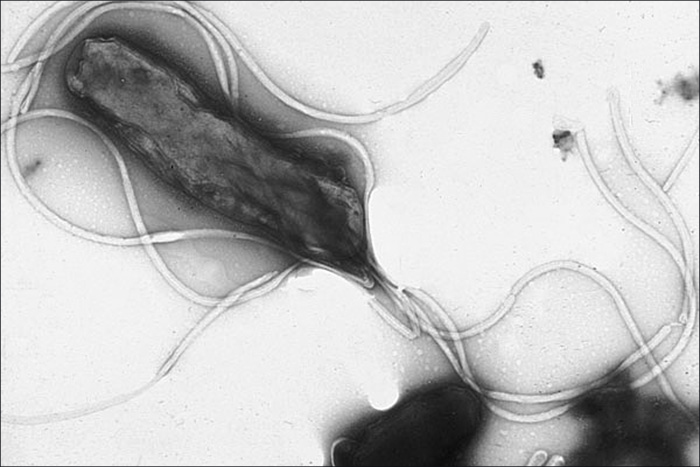

The consequences could be dire. Dr. Scott Rivkees, a former Florida surgeon general and current professor at Brown University’s School of Public Health, puts it bluntly: “Less surveillance means slower detection, which means more people get sick before we even know there’s a problem.” Consider the 2011 Listeria outbreak linked to cantaloupes, which killed 33 people before it was identified. Or the 2018 E. coli crisis in romaine lettuce, which sickened 210 across 36 states. Both were caught because of robust tracking. Now, with Campylobacter (a leading cause of diarrhea) and Vibrio (a flesh-eating bacteria linked to raw shellfish) off the radar, the next outbreak might fester unnoticed.

The immune system blind spot: Why the CDC’s germ obsession misses the mark

Here’s the uncomfortable truth: The CDC’s entire approach to foodborne illness is reactive. It waits for people to get sick, then scrambles to find the source. But what if the real problem isn’t just the germs — it’s the environment we are priming for these bacteria strains to wreck us?

Our immune systems are under siege. Processed foods laced with high-fructose corn syrup, pesticide residues, and irradiated ingredients — all blessed by the same regulatory agencies that now claim they can’t afford to track Listeria — weaken gut health, making us more vulnerable to infections.

Consider this: Norovirus, the “stomach flu” scourge of cruise ships and daycare centers, accounts for nearly half of all foodborne illnesses. Yet it’s not even a bacterium — it’s a virus, spread mostly through contaminated hands and surfaces. The CDC’s hand-washing PSAs are fine, but they ignore the elephant in the room: a diet high in refined carbs and low in fiber feeds the wrong gut bacteria, making you more susceptible to infections. Probiotics, zinc, and vitamin D — natural immune boosters — are seldom mentioned in official guidelines, despite studies showing they reduce severity and duration of foodborne illnesses.

Then there’s the irradiation paradox. The CDC and USDA approve zapping food with gamma rays to kill bacteria, but irradiation degrades nutrients and may create new, potentially harmful compounds. “It’s like using a sledgehammer to kill a fly,” says food safety advocate Mike Adams. “Instead of fixing the root cause — filthy factory farms and contaminated water — they nuke the food and call it safe.”

The six-step stomach rescue: How to fight food poisoning before it fights you

Let’s say you do get hit — maybe from undercooked chicken, a sketchy sushi roll, or that iffy potato salad at the picnic. The first 24 hours are critical. Instead of reaching for Pepto-Bismol (which merely masks symptoms), you can pre-treat your stomach to neutralize the infection before it takes hold. Here’s how:

Recognize the early warning signs: Food poisoning doesn’t always start with violent vomiting. Subtle cues — a slightly upset stomach, mild nausea, strong salivation, sweating, or a low-grade headache—can signal the first wave of bacterial invasion. Most people wait until they’re doubled over in pain, but by then, the bacteria have multiplied. Act at the first hint that something could be wrong. The quicker you detect the infection and take action, the easier it will be to recover, and the more comfortable you will be.

Activated charcoal: Mix 1 teaspoon of food-grade activated charcoal in a glass of water and drink it immediately. Charcoal binds to bacteria and toxins, preventing them from absorbing into your gut lining. Take it within 30 minutes of symptoms for maximum effect.

Ginger and gentian root: Steep 1 tablespoon of fresh grated ginger and ½ teaspoon of gentian root in hot water for 10 minutes. Strain and drink. Ginger kills bacteria while gentian root stimulates digestive juices, helping your stomach flush out pathogens. Alternatively, ginger root and gentian root powder can be mixed in water and downed quickly.

Slippery elm bark: The powdered slippery elm bark can be taken by teaspoon in a cup of water to soothe the gastrointestinal tract. The bark helps soothe the mucus membranes and bulk up the stool, assisting in the removal of bacterial wastes.

Peppermint oil: Rub twenty drops of peppermint essential oil (diluted in a carrier oil like coconut, or a water-based spray) right onto your abdomen. Peppermint relaxes intestinal muscles and calms the vagus nerve, which controls nausea.

Fast and hydrate: Skip solid food for 12–24 hours, sipping electrolyte-rich broths (bone broth or coconut water with a pinch of salt). This gives your immune system full bandwidth to fight the infection without diverting energy to digestion. Avoid food for twelve hours to prevent vomiting it back up.

These steps are tried and true for protecting you against severe illness from food poisoning. The next food poisoning outbreak might not make headlines until it’s too late. But with the right knowledge, intuition and proper action, you won’t be laid up sick, vomiting for a week – or worse.

Sources include:

Submit a correction >>

Tagged Under:

Activated Charcoal, alternative medicine, campylobacter, CDC cuts, food poisoning, gut health, herbal medicine, immune defense, listeria outbreak, natural cures, natural health, natural medicine, natural remedies, Naturopathy, Peppermint Oil, Public Health, remedies, Salmonella risk, Vibrio infection

This article may contain statements that reflect the opinion of the author