Viral pink eye seen in both symptomatic and asymptomatic coronavirus cases, making it a possible sign of infection

03/29/2020 / By Evangelyn Rodriguez

Ophthalmologists may be the first people to detect if a person is infected by the novel coronavirus. Reports have surfaced that the virus can cause pink eye or conjunctivitis, and that this may be a telltale sign of infection in people who otherwise show no coronavirus-related symptoms.

Following a surge of reported cases, the American Academy of Ophthalmology (AAO) has alerted ophthalmologists that the virus can cause mild follicular conjunctivitis, an eye disease associated with chlamydial and viral infections. One of the common symptoms of this disease is watery discharge, which can serve as a vehicle for transmission of the novel coronavirus.

Besides body fluids, the AAO said that transmission by aerosol contact with the conjunctiva — the tissue lining the insides of the eyelids — is also possible and urged ophthalmologists to protect their mouths, noses and eyes when caring for potentially infected patients.

“Patients who present to ophthalmologists for conjunctivitis who also have fever and respiratory symptoms including cough and shortness of breath, and who have recently traveled internationally, particularly to areas with known outbreaks (China, Iran, Italy and South Korea, or to hotspots within the United States), or with family members recently back from one of these areas, could represent cases of COVID-19,” warned the AAO, in an article posted on its website on March 24.

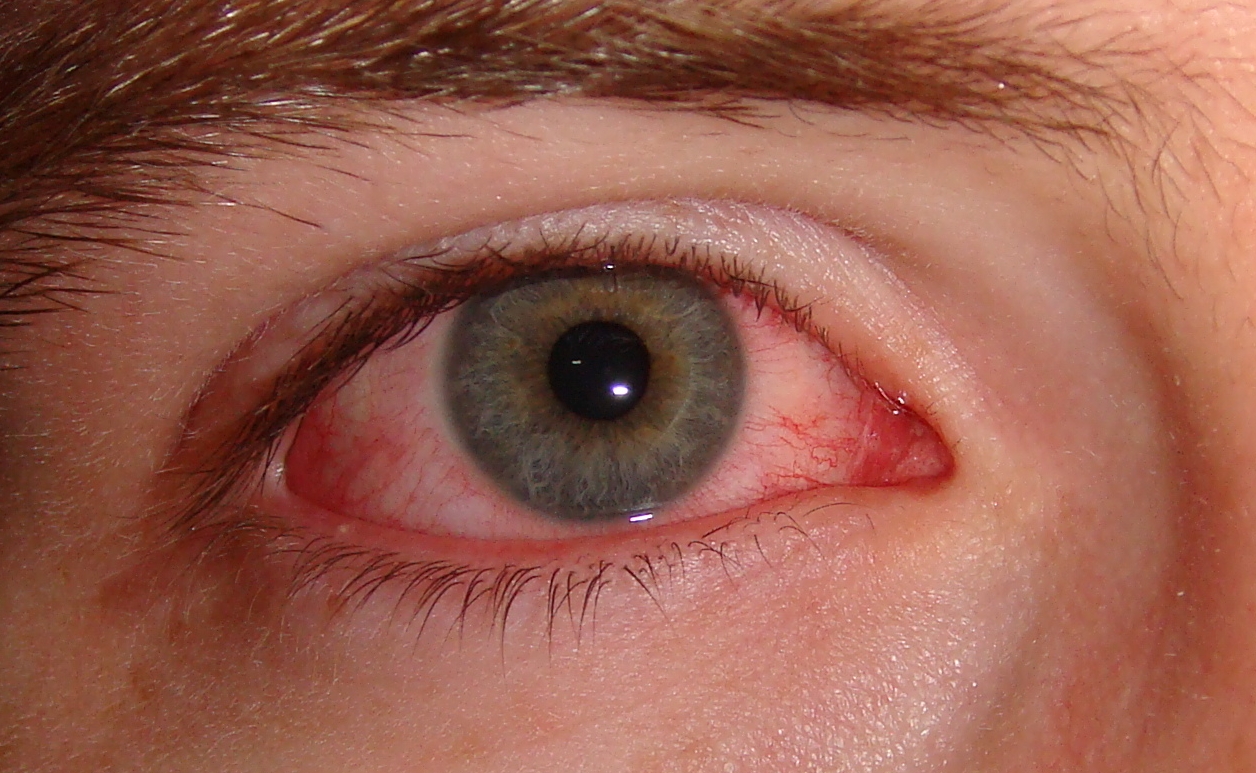

Red eyes may be a symptom of coronavirus infection

The first set of symptoms observed in patients infected by the novel coronavirus was related to respiratory illnesses. These include dry or persistent cough, breathing difficulties and abnormal chest scans, all of which are accompanied by a high fever. However, health officials began suspecting that the virus also causes viral pink eye when it was reported to develop in three percent of confirmed coronavirus cases.

On March 10, the AAO released a bulletin informing ophthalmologists and patients alike of the possibility of pink eye being a symptom of COVID-19, although it labeled the occurrence as “rare.” The AAO said that the virus can be caught by “touching fluid from an infected person’s eyes, or from objects that carry the fluid.”

A study published in The Lancet last month also reported how a member of the Chinese expert panel on pneumonia was infected by the coronavirus due to “unprotected exposure of the eyes,” after conducting an inspection at the Wuhan Fever Clinic. Days prior to the onset of pneumonia, the expert, identified as Guangfa Wang, was said to complain of redness of the eyes.

On March 24, CNN reported that “red eyes” is one of the symptoms nursing staff at the Life Care Center in Kirkland, Washington look for in their patients. According to Chelsey Earnest, a veteran registered nurse who worked there, the sickest patients all had this symptom.

“It’s something that I witnessed in all of them (the patients). They have, like … allergy eyes. The white part of the eye is not red. It’s more like they have red eye shadow on the outside of their eyes,” she said in an interview. She also described seeing patients who manifested only this symptom go to the hospital and pass away.

Besides red eyes, Earnest said infected patients at the Life Care Center presented the same clinical features: high respiratory rates, low oxygen saturation levels and dry cough. As for asymptomatic cases, she and the other staff had learned to consider red eyes as a visual cue.

Viral pink eye or any other eye issue is currently not listed by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) or the World Health Organization (WHO) as a symptom of coronavirus infection.

Ophthalmologists asked to restrict care and treatment to emergency situations

On March 18, the AAO released its recommendations regarding urgent and non-urgent patient care, asking all ophthalmologists to “cease providing any treatment other than urgent or emergent care immediately.” This recommendation was endorsed not only by the Academy Board of Trustees, but also other organizations related to ophthalmology.

The AAO cited the necessity to reduce the risk of coronavirus transmission and to conserve medical supplies as the main reason for its recommendation. Stemming the development of new cases, it said, is the only way to flatten the curve and not overwhelm the limited supply of hospital beds, ICU beds, ventilators, and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) machines in hospitals. (Related: Hospitals in NYC are nearly “maxed out” due to coronavirus infections and deaths.)

Limiting care to time-sensitive and emergent problems can also help conserve much-needed supplies, which hospitals are close to running out of. Heavily hit metropolitan areas like New York are already reeling from a widespread shortage of key equipment, which includes disposable face masks and surgical gloves. These are invaluable supplies for stopping the spread of the infectious disease and for ensuring the safety of frontline healthcare workers.

The AAO and other relevant organizations hope that by taking this critical measure, the number of ophthalmologists dying due to COVID-19 will also decrease.

“This disease is now in every state and the number of new cases is currently doubling every 1-2 days. Already, a handful of our ophthalmologist colleagues have died from COVID-19,” said the AAO in a published statement.

“It is essential that we as physicians and as responsible human beings do what we can and must to reduce virus transmission and enhance our nation’s ability to care for those desperately ill from the disease.”

Sources include:

Tagged Under: conjunctivitis, coronavirus, coronavirus transmission, covid-19, eye health, eye inflammation, health science, infections, infectious disease, medical supplies, ophthalmology, outbreak, pandemic, sickness, superbug, symptoms, viral infection, viral pink eye